In 2007, I was appointed the first Cincinnati Children’s Medical Director of Vascular Access.

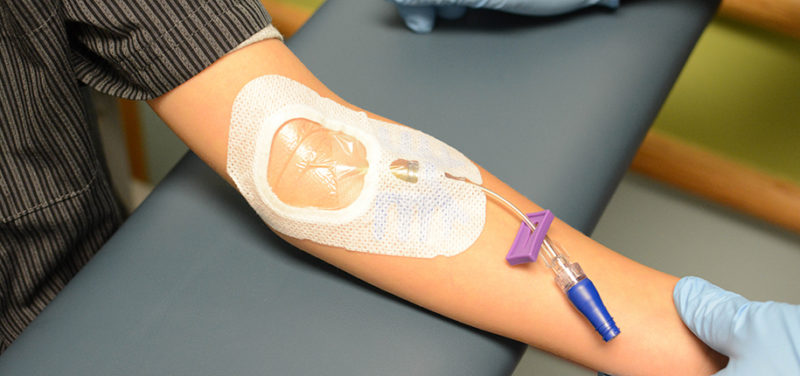

Vascular access refers to the processes and procedures required to gain and maintain safe intravenous access for patients so that medications and other important infusions can be given directly into the blood stream, usually through the venous system. Devices used to gain intravenous access range from small catheters for peripheral veins to peripherally inserted central catheters (PICC) to surgically placed central venous catheters and access ports. The most common form of vascular access is the “simple” peripheral intravenous catheter (PIV), which is the most common medical procedure performed in hospitals worldwide.

While inserting a peripheral intravenous catheter is often regarded as a minor and even trivial procedure in adults, it can be a challenging procedure in children, especially young children with chubby arms and hands where most PIV catheters are placed.

Some intravenous medications are chemically irritating to the veins and if given through a PIV for more than a short time will damage the vein, causing clots within the vein and eventually leakage of the medication into the subcutaneous tissues and skin, which can cause serious injuries.

Soon after I was appointed medical director, cases of peripheral IV injuries were reviewed by hospital senior safety and operational management. The operating room nursing vice president, Barb Tofani RN, and I were tasked with working out ways to minimize the rate of occurrence and the severity of PIV injuries at our hospital.

We undertook that task with enthusiasm and found that the then current national pediatric PIV practices and severity reporting systems were inadequate for gathering data to help us work out how to reduce injuries.

After much discussion and consultation with front line users and national colleagues, we determined that there were two main components of PIV therapy that could contribute to PIV injuries:

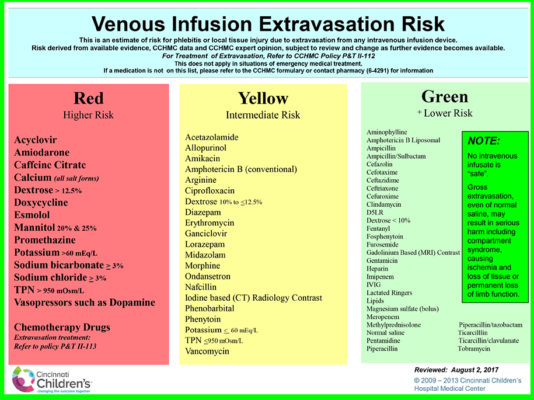

We started looking at these two components and worked to make PIV therapy as safe as possible at our hospital. We knew that some medications such as high concentration Total Parenteral Nutrition (TPN) would burn if the TPN solutions leaked under the skin, but we did not know the risk associated with many other medications.

We partnered with our pharmacy staff and the Anderson Center at Children’s and set about measuring properties such as pH and osmolarity of medications. Based on this work, we came up with a chart of “Red – Yellow – Green drugs” based on their risk for injury from extravasation, which was published and is now widely used in pediatric hospitals in the US and internationally.

The list above is posted widely throughout our hospital, especially in clinical areas where drugs or infusates are administered. Based on this list, we created some policies and guidelines such as “Red” drugs should generally not be administered for more than short periods of time through a PIV but should be administered through some form of “central” catheter – avoiding an unnecessary risk.

We worked at the same time to reduce the chances of injury based on the volume of fluid that could accumulate under the skin if a PIV malfunctioned or became dislodged. A malfunctioning PIV can cause a lot of fluid to accumulate in the subcutaneous tissues, causing pain, discomfort and eventually serious injury. A new policy of requiring bedside staff to reliably check infusing IV’s every hour was instituted. Staff was trained and performance monitored. Our experience and findings were published, aiding other institutions in reducing injury from PIV’s.

Contributed by Dr. Neil Johnson and edited by Janet Adams,(ADV TECH-ULT).